Some of the most challenging materials that diocesan archivists encounter are those that contain relics.

Every Catholic church has a relic sealed in its altar as sign of honour to the saints. The practice evokes early Christianity, when Mass was celebrated in secret over the tombs of martyrs. The sacrifice of that saint is associated with the sacrifice of Christ, celebrated on the altar during the Eucharist.

We think of altars as permanent fixtures within a church. However, in the early 20th century, Canon Law (1917) required that Mass be said over a properly consecrated altar, so movable altar stones were created in order to allow priests to celebrate Mass outside of a church. Their portable size meant the stones could be carried to any location and placed on a table or other support, creating a lawfully acceptable place for Mass.

Altar stones are book-sized blocks of marble consecrated by episcopal authority using the same ritual as a fixed altar. This included sealing first class relics (pieces of the saints' bodies, usually bones) of at least two martyred saints into a cavity in the stone. A testimonial document witnessing the stone's consecration would be sealed inside with the relic, or attached to the surface of the stone.

|

Altar Stones Collection, AS14

Altar stones are usually made of Carrara marble. The relic is cemented into a cavity along the bottom edge. |

|

Altar Stones Collection, AS40

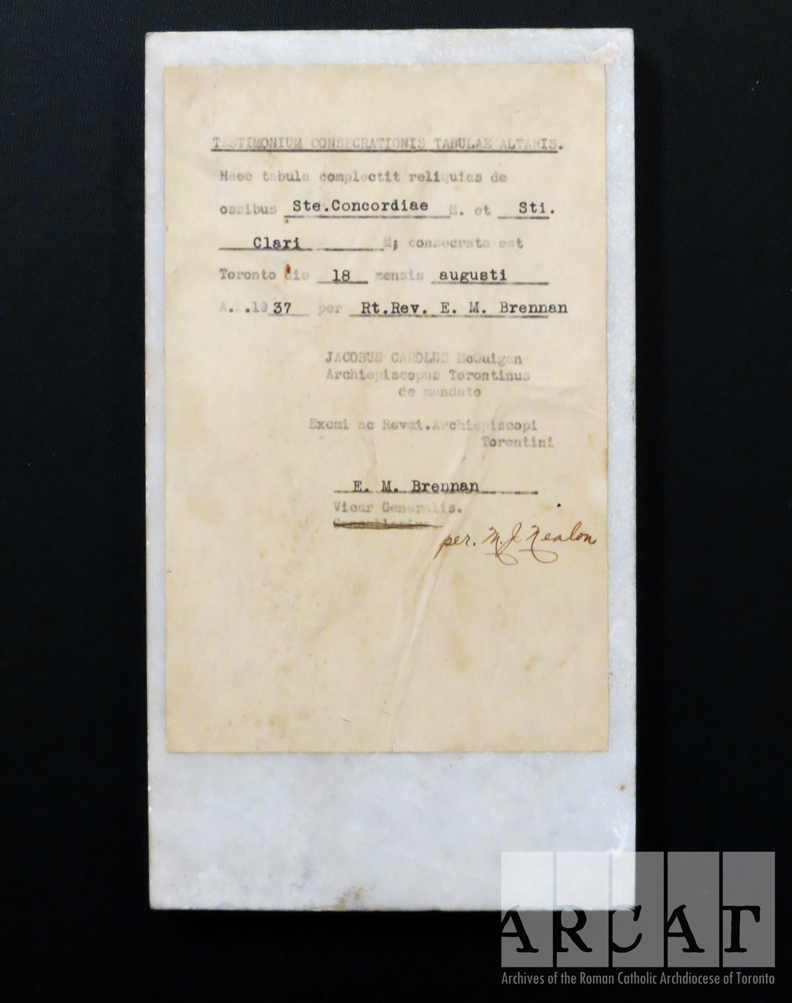

Example of a testimonium or consecration document which is often attached directly to the back the stone. This altar stone was consecrated in 1937 and contains relics from the bones of St. Concordia and St. Clarus, martyrs:

Testimonium Consecrationis Tabulae Altaris. Haec tabula complectit reliquias de ossibus Ste. Concordiae M. et Sti. Clari M.; consecrata est Toronto die 18 mensis augusti A.D. 1937 per Rt. Rev. E. M. Brennan. Jacobus Carolus McGuigan, Archiepiscopus Torontinus de mandato. Excmi ac Revmi. Archiepiscopi Torontini [signed] E. M. Brennan Vicar Generalis per M. J. Nealon. |

Falling out of use

Following Vatican II and the resulting revised edition of the Code of Canon Law (1983), the practice of using altar stones ceased and relics were required to be sealed in permanent, fixed altars only. Currently, Canon Law requires simply that an altar cloth and corporal be placed on a surface in order for Mass to be celebrated off-site.

Since portable altars were usually used by cardinals and bishops, the Chancery Office at the Archdiocese had accumulated a number of stones over the years. When altar stones went out of use, the Chancery's collection was placed in the archives. Others were donated by parishes and religious orders who no longer had need of them.

Challenges of archiving altar stones

Altar stones are different than most of the material we keep in the archives

because they contain relics, which are holy items intended for a spiritual use.

Relics are meant to be venerated rather than stored indefinitely. Therefore,

over the years, we have redistributed the altar stones to parishes

and religious communities who were dedicating new altars and needed first-class

relics. These "recycled" altar stones would have been permanently affixed or

encased in their altars.

On a practical level, the stones are large and heavy, about the size of a textbook and made of marble. Their weight must be considered when housing, storing and accessing them.

Some of the stones are not appropriate for reuse because they are damaged, the seal on the relic is loose, or the stone is missing the testimonial document that identifies the relic. It is challenging to respectfully dispose of damaged altar stones. Proper disposal includes burial on consecrated ground, since they contain holy, human remains.

We now preserve only a small sample of altar stones for posterity, as evidence of Catholic ritual practice in a certain place and time.

Newly discovered altar stone

While cleaning out the basement chapel of the Centre, an altar stone was discovered in a drawer and sent to the archives. It was consecrated by Archbishop Neil McNeil in 1924 and contains relics from the bones of St. Victoria, St. Innocent and St. Propser.

|

Altar Stones Collection, AS44

Altar stone found at the former Paulist Centre at St. Peter's Parish, Toronto. The consecration document attached reads,

Head of Wellesley Place March 26/24

The Relic of the following martyrs are entombed in the sepulchre of this altar-stone: Stae. Victoriae, Sti. Innocentii, Sti. Propseri [signed] +N. McNeil Archbishop of Toronto per T. J. Manley, Secretary

|